The funny thing about being a ContactEngine employee is that we all spend a lot of time thinking about how we can provide a good, efficient, non-annoying service with our customer communications. At the same time, we are all consumers ourselves – who among us isn’t, in this bleak capitalist hellscape we call society? – and we receive messages from companies at the same rate as everyone else, i.e. constantly. We sometimes get communications from companies that are clients of ours. This is fun, as we can predict the journey, or not fun, if we spot any typos that slipped through (this has never yet happened, but I live in fear). Most of the time though, the companies aren’t served by ContactEngine, so the messages are as new to us as anyone.

Recently, I sent out a company-wide request for examples of messages people had received in their role as consumers, so we could see how other businesses approach their communications. My colleagues obligingly swamped me in messages, which were, for varying reasons, interesting, insightful and hilarious. Some of the messages flying around the airwaves are absolute baloney, for example:

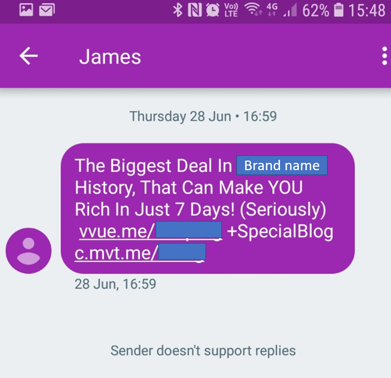

This isn’t really a fair example, I know, as it’s just possible that the above message was not sent by an official and legitimate company (Seriously). Most of the messages we looked at weren’t like this – in fact, they appeared quite normal, providing a service to the customer just as ContactEngine does. But there was still a lot of variation in the style and language, which is what we at Linguistics HQ wanted to investigate further.

We put together a few choice messages and asked our colleagues to rate them in terms of their likeability, trustworthiness, and how easy they were to understand. Results were interesting. There was general agreement across the board that, for example, shorter messages were more likeable, but longer ones were more trustworthy. Perhaps needless to say, messages that included dodgy-looking links, like in the example above, were extremely untrustworthy.

But these results were only from ContactEngine employees, a very… specific group, which, as noted, also spends a lot of time diligently thinking about customer comms. While it was an interesting start, to get a more representative idea of attitudes, we conducted a much broader online survey asking the same questions: how likeable, trustworthy and easy to understand were these messages?

Comparing the two groups, we found some definite differences. For example, people at ContactEngine were generally less trusting of messages than online respondents, which I imagine could be due to the tech-savvy approach you would expect from tech company employees. Other results were generally similar across the two groups. We were able to gain a convincing impression of which messages were viewed positively, which ones were likeable and easy to understand, and so on.

Unfortunately, I must admit that this research didn’t tell us, in objective terms, how to write a perfect message, which – being concise yet detailed, polite yet friendly, hilarious yet trustworthy and professional – would work for all people across all mediums in all situations. This may not have been a feasible goal, not yet at least.

But crucially, conducting research like this allows us to take an evidence-based approach to our conversations. For one, it showed that, as a rule, our own views may not be representative of the general public. This appears obvious, but it’s worth noting; we can’t assume that because we like something, everyone will. Even more importantly, it showed that this sort of research is necessary, because without asking people what they want, it’s impossible to know with any certainty what the best approach is. If we ask, we can learn what language people find effective and appealing, and then use that in our conversations based on objective evidence.

Open answer responses to surveys are particularly useful for this. We can use them to work out what sort of thing people see as a red flag in messages, or what they like, and use this to craft our own conversations. For example, from this survey alone we learned that people don’t trust messages which have random words capitalised; they don’t like it when texts ask you to ‘reply STOP’ to opt out; they don’t like unusual words being abbreviated; they don’t like it when the SMS is overly familiar.

This is all gold, in terms of getting a picture of how to appeal to people linguistically – or how not to piss them off. And to find out, all we had to do was ask! We’ve since been digging down into more specific research: looking into the effect of particular linguistic features, asking people to comment on the language, or even just asking them to select which messages they prefer. Breaking them down into their individual aspects like this means we can make sure that each stage of the conversation-building and personalisation process is informed by real data. This makes it more likely that customers respond, but it also means that they’ll like the messages that we send. It’s not only about being a functional, efficient service, but a likeable one as well. Not as easily measurable, but arguably no less important, if we want to cling on to the remaining shreds of humanity left in this aforementioned capitalist hellscape.